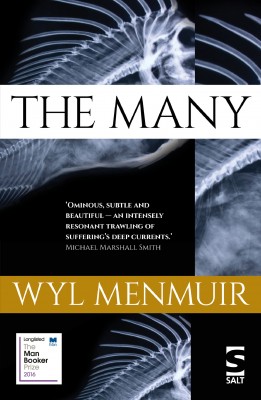

In a small coastal village somewhere in Britain, a stranger arrives, moving into a cottage left vacant by the death of a fisherman years earlier. Meanwhile, the village’s diminishing fishing fleet is confined to the coastal waters by a silent barricade of tankers in the distance, and what catch it manages to return appears mysteriously diseased. Told from the alternative points of view of the stranger, Timothy, and a fisherman, Ethan, we gradually learn about the events that have brought the characters to this point.

This is a novel in search of itself. It’s trying desperately to achieve significance through simplicity, but the details never come together. The psychology is strained and rings false; the coincidences tug at the seams of the narrative instead of anchoring it. When a book is this short and so little happens in it, it’s essential that every single detail is invested with the truth of the whole. Instead, they’re hollow starting at the minutiae and working outwards. Subtext is unnecessarily made explicit – a literary crime when the tone you’re aiming at is a gentle meditation on loss. There are jarring grammatical errors that the editor’s red pencil presumably missed. It feels like nothing so much as a first novel. Supposedly the author wrote it in the back of a campervan after he took an online creative writing course. With all due respect to campervans and online education, I have no problem believing either of those facts.

Possibly part of the problem is that the two books I read before it were Eileen and My Name is Lucy Barton – two very different novels, but two acute psychological portraits that hang together with the effortless grace of an Olympic figure skater. The Many did NOT compare favourably. It was like two thoroughbreds standing next to a pantomime horse.

Somehow this made the Booker longlist. For the first time I find myself hoping some American novels make it to the shortlist.