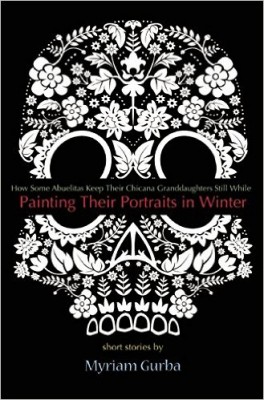

In the first story of this collection, the narrator/author’s grandmother (Abuelita), an artist, has her young granddaughters pose for her. In order to keep them from fidgeting, as she paints, she tells them increasingly gruesome Mexican fairytales; appalled and fascinated, they beg for more.

The rest of the book takes its tonal cue from this first story, combining semi-autobiography, post-colonial commentary, family anecdote, and folk legend. The narrator/author is a LesbiMexiPolMerican (I’m pretty sure she would approve this label, based on one of the stories in which she describes her crush on a “Moth”: Mexican Goth) and the stories, which follow her and her family from childhood in the US and Mexico through adolescence and into early adulthood, trace the emergence of this identity and of her interaction with it, as well as her growing awareness of herself as a woman in a world of men.

That might sound a bit heavy, and it is at times. Most, if not all, of the stories contain an undercurrent of barely-suppressed feminine rage; the miracle is that the author’s dexterity manages to keep the focus on the narrative, and the stories aren’t swept away by it. In one early story, after she goes ice-skating with her cousins, the narrator’s aunt’s car is threatened by men with automatic weapons. They manage to drive off, leaving the attackers behind them pointing their guns at other women. They get home, and the narrator searches in vain for news of the attack on the television. Her Abuelito literally chuckles and pats her head: “that’s not going to be on TV”.

Luckily, the collection is also tempered with honest-to-God hilarity. The characters of her family are both universal and culturally-rooted; I particularly love her father and his obsession with planting climate-appropriate plants in his Californian garden. I had to stop myself underlining every sentence in that particular story. Witness:

“Maybe lawn mowing turned me gay. Since I was the eldest, Dad handed me the mower. I pushed it forward and right, forward and right, losing some hearing, losing my heterosexuality as grass bled onto my sneakers. My calves, hips, and ass grew toned. I shed blubber. I shed any attraction I had to boys. Jelly stained my underwear. I mowed the lawn with cramps. I weedwacked hard-to-reach tufts. I wielded the leaf blower, pointed it at tree skirts. Have you ever seen a twelve-year-old girl with a leaf blower? It’s butch.”

I’m on record as not loving short fiction as a genre. I mean that literally: I like it fine, I just don’t love it in the way that I love novels. But I loved this collection. I loved the voice of the narrator, self-aware, ironic, but in deadly earnest about the things that matter. I loved the use of folklore, the way it weaves in and out of the stories and roots them, reflecting the way the same folk stories anchored the narrator’s childhood and her relationship with her extended family. I loved her portrayal of her family, realism tempered with affection, their recognisable foibles mixed with their other-ness. A strong and engaging book.