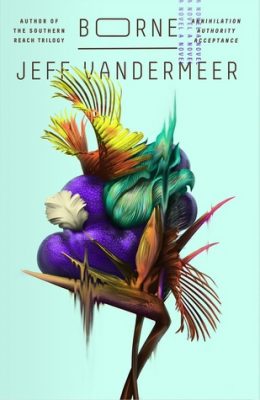

Borne is the new novel from Jeff VanderMeer, the David Lynch of literary sci fi. Don’t know what I mean? Let me give you an example by summarizing the events leading up to the action in this book. In a post-apocalyptic world devastated by climate change and other, unspecified man-made disasters, an unnamed, partially-destroyed city is dominated by a biotech company (known, of course, as the Company). It’s not clear exactly what the Company makes (drugs? weapons? designer pets?), but at some point it creates Mord, a thing which grows into a giant bear the size of a building (it’s described as being three storeys high lying down). Mord develops the power to levitate and escapes the Company, wreaking havoc and destroying what remains of civilization in the city. In this environment our protagonist, a black (yes!) woman (YES!) named Rachel (fine), pairs up with Wick, a disgraced former Company employee who now manufactures biological hallucinogens in the form of beetles you insert into your ear, in a converted swimming pool that he’s made into a kind of swamp teeming with artificial life. They live in an apartment complex camouflaged as a cliff face overlooking a toxic river, which they’ve booby-trapped with weaponised biochemistry and other deterrents against trespassers. To help Wick, Rachel works as a scavenger, searching for biotech that can go into his drug-swamp-brew. The most fruitful source of this is Mord himself, and while he sleeps, Rachel climbs around in his fur looking for anything salvageable. Then comes page one.

So yeah, it’s a bit weirder than your average speculative fiction. But like all decent speculative fiction, Borne uses extraordinary circumstances to explore universal themes: in this case, the key questions are, What does it mean to be human? and, What makes a good parent? Borne is what Rachel finds in Mord’s fur on that first page, and he (it, really, but she thinks of it as he) is clearly artificially created, a thing that looks at first like a sea anemone but gradually develops into…something else. Rachel attempts to instill her values into Borne, educating him and teaching him right and wrong, but it’s clear he’s been designed by the Company to be a thing altogether different from a junior, squiddy version of Rachel. On the other hand, it’s also clear that her raising of him has not left him unchanged, as he resists his “true” “nature” as well as developing some characteristics traditionally associated with humanity. Ultimately, all of their fates might rest on whether her parenting of Borne was successful or not (something I imagine might plague the nightmares of a good many parents).

For me, a non-parent, the question about personhood is probably the more interesting. Borne, an artificially-created entity, asks Rachel whether he’s a person. Her answer is a hinge on which much in the book turns: he’s not human, but he is a person. On another occasion, she says, “You are a person. But like a person, you can be a weapon, too.” As in a lot of science fiction, barely anybody in the book is wholly a natural person. Wick is one obvious example: he’s sick, and inhabited by biotechnology (things like worms and insects) that carries out continual diagnosis and treatment on him. The drugs he manufactures remove certain memories and replace them with false ones. Both biologically and psychologically, he is artificially maintained. Is he more or less a person than Borne? In another scene, Rachel is attacked by a group of feral children who are too young to have ever lived in a stable society. They physically torture her, but don’t rape her; reflecting on this, she concludes that there wasn’t enough in them that was human to think of rape. So what makes being a person such a desirable thing?

Vandermeer’s fan favourite Annihilation, the first novel in his Southern Reach trilogy, will be released next year as a film directed by Alex Garland and starring (inter alia) Natalie Portman and (one for you Jane the Virgin fans) Gina Rodriguez. I have literally no idea how this is even possible, given the hallucinatory quality of much of the trilogy; it’s a page-turner, but it has things like a structure that some people describe as a tower and others as a tunnel descending into the earth, not to mention having no stated purpose or particular resolution. The written word can accommodate those things; it’s hard to imagine what a visual medium will make of them. I raise this as a comparison. Borne is a much more reader-friendly experience, in that it’s possible, after reading it, to describe what happened. There are some mysteries that go unresolved, but the main story elements come to a satisfying conclusion, and even the stuff that stays ambiguous is possible to express as a question in human language. All of which makes this novel a good introduction to the weirder side of serious sci fi literature, not to mention satisfying in a slightly dreamy, sometimes absurd way.